Cooling tower

Cooling towers are heat removal devices used to transfer process waste heat to the atmosphere. Cooling towers may either use the evaporation of water to remove process heat and cool the working fluid to near the wet-bulb air temperature or rely solely on air to cool the working fluid to near the dry-bulb air temperature. Common applications include cooling the circulating water used in oil refineries, chemical plants, power stations and building cooling. The towers vary in size from small roof-top units to very large hyperboloid structures (as in Image 1) that can be up to 200 metres tall and 100 metres in diameter, or rectangular structures (as in Image 2) that can be over 40 metres tall and 80 metres long. Smaller towers are normally factory-built, while larger ones are constructed on site. They are often associated with nuclear power plants in popular culture.

A hyperboloid cooling tower was patented by Frederik van Iterson and Gerard Kuypers in 1918. [1]

Classification by use

Cooling towers can generally be classified by use into either HVAC (air-conditioning) or industrial duty as suggested by Rantael, Rogellito and Stronghold, April in the book The Mystery of Cooling Towers Unfolded.

HVAC

An HVAC cooling tower is a subcategory rejecting heat from a chiller. Water-cooled chillers are normally more energy efficient than air-cooled chillers due to heat rejection to tower water at or near wet-bulb temperatures. Air-cooled chillers must reject heat at the dry-bulb temperature, and thus have a lower average reverse-Carnot cycle effectiveness. Large office buildings, hospitals, and schools typically use one or more cooling towers as part of their air conditioning systems. Generally, industrial cooling towers are much larger than HVAC towers.

HVAC use of a cooling tower pairs the cooling tower with a water-cooled chiller or water-cooled condenser. A ton of air-conditioning is the removal of 12,000 Btu/hour (3517 W). The equivalent ton on the cooling tower side actually rejects about 15,000 Btu/hour (4396 W) due to the heat-equivalent of the energy needed to drive the chiller's compressor. This equivalent ton is defined as the heat rejection in cooling 3 U.S. gallons/minute (1,500 pound/hour) of water 10 °F (5.56 °C), which amounts to 15,000 Btu/hour, or a chiller coefficient-of-performance (COP) of 4.0. This COP is equivalent to an energy efficiency ratio (EER) of 13.65.

Cooling towers are also used in HVAC systems that have multiple water source heat pumps that share a common piping "loop". In this type of system the cooling tower is used to remove the heat that is generated whenever the heat pumps are in the cooling mode.

Industrial cooling towers

Industrial cooling towers can be used to remove heat from various sources such as machinery or heated process material. The primary use of large, industrial cooling towers is to remove the heat absorbed in the circulating cooling water systems used in power plants, petroleum refineries, petrochemical plants, natural gas processing plants, food processing plants, semi-conductor plants, and for other industrial facilities such as in condensers of distillation columns, for cooling liquid in crystallization, etc.[2] The circulation rate of cooling water in a typical 700 MW coal-fired power plant with a cooling tower amounts to about 71,600 cubic metres an hour (315,000 U.S. gallons per minute)[3] and the circulating water requires a supply water make-up rate of perhaps 5 percent (i.e., 3,600 cubic metres an hour).

If that same plant had no cooling tower and used once-through cooling water, it would require about 100,000 cubic metres an hour [4] and that amount of water would have to be continuously returned to the ocean, lake or river from which it was obtained and continuously re-supplied to the plant. Furthermore, discharging large amounts of hot water may raise the temperature of the receiving river or lake to an unacceptable level for the local ecosystem. Elevated water temperatures can kill fish and other aquatic organisms. (See thermal pollution.) A cooling tower serves to dissipate the heat into the atmosphere instead and wind and air diffusion spreads the heat over a much larger area than hot water can distribute heat in a body of water. Some coal-fired and nuclear power plants located in coastal areas do make use of once-through ocean water. But even there, the offshore discharge water outlet requires very careful design to avoid environmental problems.

Petroleum refineries also have very large cooling tower systems. A typical large refinery processing 40,000 metric tonnes of crude oil per day (300,000 barrels per day) circulates about 80,000 cubic metres of water per hour through its cooling tower system.

The world's tallest cooling tower is the 200 metre tall cooling tower of Niederaussem Power Station.

Heat transfer methods

With respect to the heat transfer mechanism employed, the main types are:

- Wet cooling towers or simply cooling towers operate on the principle of evaporation. The working fluid and the evaporated fluid (usually H2O) are one and the same.

- Dry coolers operate by heat transfer through a surface that separates the working fluid from ambient air, such as in a heat exchanger, utilizing convective heat transfer. They do not use evaporation.

- Fluid coolers are hybrids that pass the working fluid through a tube bundle, upon which clean water is sprayed and a fan-induced draft applied. The resulting heat transfer performance is much closer to that of a wet cooling tower, with the advantage provided by a dry cooler of protecting the working fluid from environmental exposure.

In a wet cooling tower, the warm water can be cooled to a temperature lower than the ambient air dry-bulb temperature, if the air is relatively dry. (see: dew point and psychrometrics). As ambient air is drawn past a flow of water, evaporation occurs. Evaporation results in saturated air conditions, lowering the temperature of the water to the wet bulb air temperature, which is lower than the ambient dry bulb air temperature, the difference determined by the humidity of the ambient air.

To achieve better performance (more cooling), a medium called fill is used to increase the surface area between the air and water flows. Splash fill consists of material placed to interrupt the water flow causing splashing. Film fill is composed of thin sheets of material upon which the water flows. Both methods create increased surface area.

Air flow generation methods

With respect to drawing air through the tower, there are three types of cooling towers:

- Natural draft, which utilizes buoyancy via a tall chimney. Warm, moist air naturally rises due to the density differential to the dry, cooler outside air. Warm moist air is less dense than drier air at the same pressure. This moist air buoyancy produces a current of air through the tower.

- Mechanical draft, which uses power driven fan motors to force or draw air through the tower.

- Induced draft: A mechanical draft tower with a fan at the discharge which pulls air through tower. The fan induces hot moist air out the discharge. This produces low entering and high exiting air velocities, reducing the possibility of recirculation in which discharged air flows back into the air intake. This fan/fin arrangement is also known as draw-through. (see Image 2, 3)

- Forced draft: A mechanical draft tower with a blower type fan at the intake. The fan forces air into the tower, creating high entering and low exiting air velocities. The low exiting velocity is much more susceptible to recirculation. With the fan on the air intake, the fan is more susceptible to complications due to freezing conditions. Another disadvantage is that a forced draft design typically requires more motor horsepower than an equivalent induced draft design. The forced draft benefit is its ability to work with high static pressure. They can be installed in more confined spaces and even in some indoor situations. This fan/fill geometry is also known as blow-through. (see Image 4)

- Fan assisted natural draft. A hybrid type that appears like a natural draft though airflow is assisted by a fan.

Hyperboloid (a.k.a. hyperbolic) cooling towers (Image 1) have become the design standard for all natural-draft cooling towers because of their structural strength and minimum usage of material. The hyperboloid shape also aids in accelerating the upward convective air flow, improving cooling efficiency. They are popularly associated with nuclear power plants. However, this association is misleading, as the same kind of cooling towers are often used at large coal-fired power plants as well. Similarly, not all nuclear power plants have cooling towers, instead cooling their heat exchangers with lake, river or ocean water.

Categorization by air-to-water flow

Crossflow

Crossflow is a design in which the air flow is directed perpendicular to the water flow (see diagram below). Air flow enters one or more vertical faces of the cooling tower to meet the fill material. Water flows (perpendicular to the air) through the fill by gravity. The air continues through the fill and thus past the water flow into an open plenum area. A distribution or hot water basin consisting of a deep pan with holes or nozzles in the bottom is utilized in a crossflow tower. Gravity distributes the water through the nozzles uniformly across the fill material.

Counterflow

In a counterflow design the air flow is directly opposite to the water flow (see diagram below). Air flow first enters an open area beneath the fill media and is then drawn up vertically. The water is sprayed through pressurized nozzles and flows downward through the fill, opposite to the air flow.

Common to both designs:

- The interaction of the air and water flow allow a partial equalization and evaporation of water.

- The air, now saturated with water vapor, is discharged from the cooling tower.

- A collection or cold water basin is used to contain the water after its interaction with the air flow.

Both crossflow and counterflow designs can be used in natural draft and mechanical draft cooling towers.

Cooling tower as a flue gas stack

At some modern power stations, equipped with flue gas purification like the Power Station Staudinger Grosskrotzenburg and the Power Station Rostock, the cooling tower is also used as a flue gas stack (industrial chimney). At plants without flue gas purification, problems with corrosion may occur.

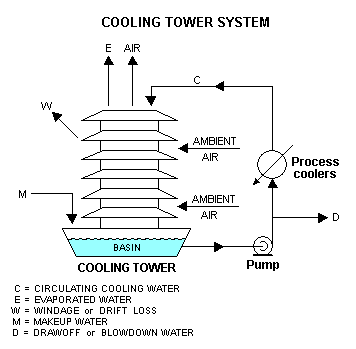

Wet cooling tower material balance

Quantitatively, the material balance around a wet, evaporative cooling tower system is governed by the operational variables of makeup flow rate, evaporation and windage losses, draw-off rate, and the concentration cycles:[5]

| M | = Make-up water in m³/h |

| C | = Circulating water in m³/h |

| D | = Draw-off water in m³/h |

| E | = Evaporated water in m³/h |

| W | = Windage loss of water in m³/h |

| X | = Concentration in ppmw (of any completely soluble salts … usually chlorides) |

| XM | = Concentration of chlorides in make-up water (M), in ppmw |

| XC | = Concentration of chlorides in circulating water (C), in ppmw |

| Cycles | = Cycles of concentration = XC / XM (dimensionless) |

| ppmw | = parts per million by weight |

In the above sketch, water pumped from the tower basin is the cooling water routed through the process coolers and condensers in an industrial facility. The cool water absorbs heat from the hot process streams which need to be cooled or condensed, and the absorbed heat warms the circulating water (C). The warm water returns to the top of the cooling tower and trickles downward over the fill material inside the tower. As it trickles down, it contacts ambient air rising up through the tower either by natural draft or by forced draft using large fans in the tower. That contact causes a small amount of the water to be lost as windage (W) and some of the water (E) to evaporate. The heat required to evaporate the water is derived from the water itself, which cools the water back to the original basin water temperature and the water is then ready to recirculate. The evaporated water leaves its dissolved salts behind in the bulk of the water which has not been evaporated, thus raising the salt concentration in the circulating cooling water. To prevent the salt concentration of the water from becoming too high, a portion of the water is drawn off (D) for disposal. Fresh water makeup (M) is supplied to the tower basin to compensate for the loss of evaporated water, the windage loss water and the draw-off water.

A water balance around the entire system is:

- M = E + D + W

Since the evaporated water (E) has no salts, a chloride balance around the system is:

- M (XM) = D (XC) + W (XC) = XC (D + W)

and, therefore:

- XC / XM = Cycles of concentration = M ÷ (D + W) = M ÷ (M – E) = 1 + [E ÷ (D + W)]

From a simplified heat balance around the cooling tower:

- E = C · ΔT · cp ÷ HV

| where: | |

| HV | = latent heat of vaporization of water = ca. 2260 kJ / kg |

| ΔT | = water temperature difference from tower top to tower bottom, in °C |

| cp | = specific heat of water = ca. 4.184 kJ / (kg °C) °C) |

Windage (or drift) losses (W) from large-scale industrial cooling towers, in the absence of manufacturer's data, may be assumed to be:

- W = 0.3 to 1.0 percent of C for a natural draft cooling tower without windage drift eliminators

- W = 0.1 to 0.3 percent of C for an induced draft cooling tower without windage drift eliminators

- W = about 0.005 percent of C (or less) if the cooling tower has windage drift eliminators

Cycles of concentration represents the accumulation of dissolved minerals in the recirculating cooling water. Draw-off (or blowdown) is used principally to control the buildup of these minerals.

The chemistry of the makeup water including the amount of dissolved minerals can vary widely. Makeup waters low in dissolved minerals such as those from surface water supplies (lakes, rivers etc.) tend to be aggressive to metals (corrosive). Makeup waters from ground water supplies (wells) are usually higher in minerals and tend to be scaling (deposit minerals). Increasing the amount of minerals present in the water by cycling can make water less aggressive to piping however excessive levels of minerals can cause scaling problems.

As the cycles of concentration increase the water may not be able to hold the minerals in solution. When the solubility of these minerals have been exceeded they can precipitate out as mineral solids and cause fouling and heat exchange problems in the cooling tower or the heat exchangers. The temperatures of the recirculating water, piping and heat exchange surfaces determine if and where minerals will precipitate from the recirculating water. Often a professional water treatment consultant will evaluate the makeup water and the operating conditions of the cooling tower and recommend an appropriate range for the cycles of concentration. The use of water treatment chemicals, pretreatment such as water softening, pH adjustment, and other techniques can affect the acceptable range of cycles of concentration.

Concentration cycles in the majority of cooling towers usually range from 3 to 7. In the United States the majority of water supplies are well waters and have significant levels of dissolved solids. On the other hand one of the largest water supplies, New York City, has a surface supply quite low in minerals and cooling towers in that city are often allowed to concentrate to 7 or more cycles of concentration.

Besides treating the circulating cooling water in large industrial cooling tower systems to minimize scaling and fouling, the water should be filtered and also be dosed with biocides and algaecides to prevent growths that could interfere with the continuous flow of the water.[5] For closed loop evaporative towers, corrosion inhibitors may be used, but caution should be taken to meet local environmental regulations as some inhibitors use chromates.

Ambient conditions dictate the efficiency of any given tower due to the amount of water vapor the air is able to absorb and hold, as can be determined on a psychrometric chart.

Cooling towers and Legionnaires' disease

Another very important reason for using biocides in cooling towers is to prevent the growth of Legionella, including species that cause legionellosis or Legionnaires' disease, most notably L. pneumophila.[6] The various Legionella species are the cause of Legionnaires' disease in humans and transmission is via exposure to aerosols—the inhalation of mist droplets containing the bacteria. Common sources of Legionella include cooling towers used in open recirculating evaporative cooling water systems, domestic hot water systems, fountains, and similar disseminators that tap into a public water supply. Natural sources include freshwater ponds and creeks.

French researchers found that Legionella spread through the air up to 6 kilometres from a large contaminated cooling tower at a petrochemical plant in Pas-de-Calais, France. That outbreak killed 21 of the 86 people that had a laboratory-confirmed infection.[7]

Drift (or windage) is the term for water droplets of the process flow allowed to escape in the cooling tower discharge. Drift eliminators are used in order to hold drift rates typically to 0.001%-0.005% of the circulating flow rate. A typical drift eliminator provides multiple directional changes of airflow while preventing the escape of water droplets. A well-designed and well-fitted drift eliminator can greatly reduce water loss and potential for Legionella or other chemical exposure.

Many governmental agencies, cooling tower manufacturers and industrial trade organizations have developed design and maintenance guidelines for preventing or controlling (by using Neosens FS sensor for example, the growth of Legionella in cooling towers. Below is a list of sources for such guidelines:

- Centers for Disease Control and PreventionPDF (1.35 MB) - Procedure for Cleaning Cooling Towers and Related Equipment (pages 239 and 240 of 249)

- Cooling Technology InstitutePDF (240 KB) - Best Practices for Control of Legionella, July, 2006

- Association of Water TechnologiesPDF (964 KB) - Legionella 2003

- California Energy CommissionPDF (194 KB) - Cooling Water Management Program Guidelines For Wet and Hybrid Cooling Towers at Power Plants

- SPX Cooling TechnologiesPDF (119 KB) - Cooling Towers Maintenance Procedures

- SPX Cooling TechnologiesPDF (789 KB) - ASHRAE Guideline 12-2000 - Minimizing the Risk of Legionellosis

- SPX Cooling TechnologiesPDF (83.1 KB) - Cooling Tower Inspection Tips {especially page 3 of 7}

- Tower Tech Modular Cooling TowersPDF (109 KB) - Legionella Control

- GE Infrastructure Water & Process Technologies Betz DearbornPDF (195 KB) - Chemical Water Treatment Recommendations For Reduction of Risks Associated with Legionella in Open Recirculating Cooling Water Systems

Cooling tower fog

Under certain ambient conditions, plumes of water vapor (fog) can be seen rising out of the discharge from a cooling tower (see Image 1), and can be mistaken as smoke from a fire. If the outdoor air is at or near saturation, and the tower adds more water to the air, saturated air with liquid water droplets can be discharged—what is seen as fog. This phenomenon typically occurs on cool, humid days, but is rare in many climates.

Cooling tower operation in freezing weather

Cooling towers with malfunctions can freeze during very cold weather. Typically, freezing starts at the corners of a cooling tower with a reduced or absent heat load. Increased freezing conditions can create growing volumes of ice, resulting in increased structural loads. During the winter, some sites continuously operate cooling towers with 40 °F (4 °C) water leaving the tower. Basin heaters, tower draindown, and other freeze protection methods are often employed in cold climates.

- Do not operate the tower unattended.

- Do not operate the tower without a heat load. This can include basin heaters and heat trace. Basin heaters maintain the temperature of the water in the tower pan at an acceptable level. Heat trace is a resistive element that runs along water pipes located in cold climates to prevent freezing.

- Maintain design water flow rate over the fill.

- Manipulate airflow to maintain water temperature above freezing point.[8]

Some commonly used terms in the cooling tower industry

- Drift - Water droplets that are carried out of the cooling tower with the exhaust air. Drift droplets have the same concentration of impurities as the water entering the tower. The drift rate is typically reduced by employing baffle-like devices, called drift eliminators, through which the air must travel after leaving the fill and spray zones of the tower. Drift can also be reduced by using warmer entering cooling tower temperatures.

- Blow-out - Water droplets blown out of the cooling tower by wind, generally at the air inlet openings. Water may also be lost, in the absence of wind, through splashing or misting. Devices such as wind screens, louvers, splash deflectors and water diverters are used to limit these losses.

- Plume - The stream of saturated exhaust air leaving the cooling tower. The plume is visible when water vapor it contains condenses in contact with cooler ambient air, like the saturated air in one's breath fogs on a cold day. Under certain conditions, a cooling tower plume may present fogging or icing hazards to its surroundings. Note that the water evaporated in the cooling process is "pure" water, in contrast to the very small percentage of drift droplets or water blown out of the air inlets.

- Blow-down - The portion of the circulating water flow that is removed in order to maintain the amount of dissolved solids and other impurities at an acceptable level. It may be noted that higher TDS (total dissolved solids) concentration in solution results in greater potential cooling tower efficiency. However the higher the TDS concentration, the greater the risk of scale, biological growth and corrosion.

- Leaching - The loss of wood preservative chemicals by the washing action of the water flowing through a wood structure cooling tower.

- Noise - Sound energy emitted by a cooling tower and heard (recorded) at a given distance and direction. The sound is generated by the impact of falling water, by the movement of air by fans, the fan blades moving in the structure, and the motors, gearboxes or drive belts.

- Approach - The approach is the difference in temperature between the cooled-water temperature and the entering-air wet bulb temperature (twb). Since the cooling towers are based on the principles of evaporative cooling, the maximum cooling tower efficiency depends on the wet bulb temperature of the air. The wet-bulb temperature is a type of temperature measurement that reflects the physical properties of a system with a mixture of a gas and a vapor, usually air and water vapor

- Range - The range is the temperature difference between the water inlet and water exit.

- Fill - Inside the tower, fills are added to increase contact surface as well as contact time between air and water. Thus they provide better heat transfer. The efficiency of the tower also depends on them. There are two types of fills that may be used:

- Film type fill (causes water to spread into a thin film)

- Splash type fill (breaks up water and interrupts its vertical progress)

Fire hazards

Cooling towers which are constructed in whole or in part of combustible materials can support propagating internal fires. The resulting damage can be sufficiently severe to require the replacement of the entire cell or tower structure. For this reason, some codes and standards[9] recommend combustible cooling towers be provided with an automatic fire sprinkler system. Fires can propagate internally within the tower structure during maintenance when the cell is not in operation (such as for maintenance or construction), and even when the tower is in operation, especially those of the induced-draft type because of the existence of relatively dry areas within the towers[10].

Stability

Being very large structures, they are susceptible to wind damage, and several spectacular failures have occurred in the past. At Ferrybridge power station on 1 November 1965, the station was the site of a major structural failure, when three of the cooling towers collapsed due to vibrations in 85mph winds. Although the structures had been built to withstand higher wind speeds, the shape of the cooling towers meant that westerly winds were funnelled into the towers themselves, creating a vortex. Three out of the original eight cooling towers were destroyed and the remaining five were severely damaged. The towers were rebuilt and all eight cooling towers were strengthened to tolerate adverse weather conditions. Building codes were changed to include improved structural support, and wind tunnel tests introduced to check tower structures and configuration.

See also

- Architectural engineering

- Cooling water

- Deep lake water cooling

- Evaporative cooler

- Fossil fuel power plant

- HVAC (Heating, ventilating and air conditioning)

- Hyperboloid structure

- Mechanical engineering

- Power station

- Willow Island disaster

References

- ↑ UK Patent No. 108,863

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). (1997) Profile of the Fossil Fuel Electric Power Generation Industry. Washington, D.C. (Report). Document No. EPA/310-R-97-007. p. 79.

- ↑ Cooling System Retrofit Costs EPA Workshop on Cooling Water Intake Technologies, John Maulbetsch, Maulbetsch Consulting, May 2003

- ↑ Thomas J. Feeley, III, Lindsay Green, James T. Murphy, Jeffrey Hoffmann, and Barbara A. Carney (2005). "Department of Energy/Office of Fossil Energy’s Power Plant Water Management R&D Program." U.S. Department of Energy, July 2005.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Beychok, Milton R. (1967). Aqueous Wastes from Petroleum and Petrochemical Plants (1st Edition ed.). John Wiley and Sons. LCCN 67019834. (available in many university libraries)

- ↑ Ryan K.J.; Ray C.G. (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th Edition ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- ↑ Airborne Legionella May Travel Several Kilometers (access requires free registration)

- ↑ SPX Cooling Technologies: Operating Cooling Towers in Freezing WeatherPDF (1.45 MB)

- ↑ National Fire Protection Association (NFPA). NFPA 214, Standard on Water-Cooling Towers.

- ↑ NFPA 214, Standard on Water-Cooling Towers. Section A1.1

External links

- Cooling Towers: Design and Operation Considerations

- What is a cooling tower? - Cooling Technology Institute

- "Cooling Towers" - includes diagrams - Virtual Nuclear Tourist

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||